In the late night hours of August, meteors can be seen darting across the northeast sky. What traces do these heavenly bodies leave behind – in myths, literature and on the Earth itself? The NL has tracked these celestial messengers in the digital newspaper archive.

Every month, the Mirasteilas Observatory (GR) sights up to 900 meteoroids – what meteors are called before they enter the Earth’s atmosphere. Once these bodies hit the ground, they are known as meteorites. There have been eleven confirmed meteorite crashes on Swiss soil. Every day, around 1,000 to 6,500 tonnes of material from outer space rains down on our planet. Considering the amounts, it is astonishing that meteorites only rarely make their physical impact felt. However, these heavenly bodies have been a source of inspiration for humanity for eons.

Meteor-wrongs and literary inspiration

The significance that people attribute to “shooting stars” has always been contradictory. Some saw them as divine sparks, while others considered them to be bringers of mischief or signs that the sky was about to fall.

Meteor” (Ominous meteor), 1980, gouache

on cardboard

© CDN/Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft

A mythical flash in the heavens was described in Switzerland in 1421: a farmer by the name of Stämpfli spotted the figure of a fire-breathing dragon in the sky near Rothenburg. The dragon supposedly dropped something that fell to the Earth, causing Stämpfli to pass out from sheer fright. When he regained consciousness, he found a round stone with a peculiar pattern lying next to him: the Dragon’s Eye of Lucerne. However, this story remains in the realm of legend, and the stone was revealed to be a “meteor-wrong”, i.e., not actually a meteorite at all.

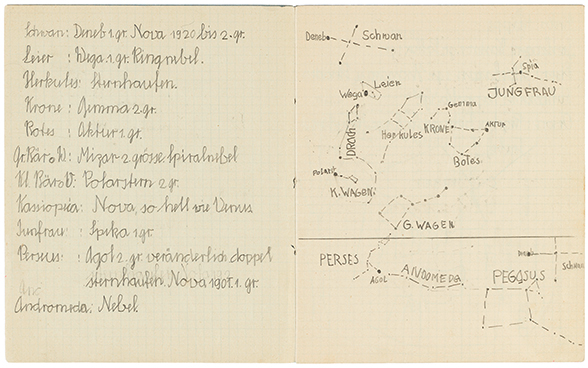

These heavenly bodies have also left an impact in Swiss art and literature. Author Friedrich Dürrenmatt, for instance, showed an interest in astronomy as a young pupil. In his later works, he used the impact of a meteorite as a metaphor for the unexpected and unpredictable.

Traces of the heavens on Swiss soil

The rare instances when people and meteorites meet are usually less dramatic. Reto Merlo from Grüningen (ZH) stumbled upon a 4.87-gram stone on Le Chasseron (VD) during a school trip to the mountains in the summer of 1959. He glued it to a wooden board and kept it there until 2017. After reading about meteorites, he sent the stone to the Natural History Museum Bern, which then forwarded it to the University of Lausanne. This particular rock turned out to be a beautifully coloured meteorite.

On an afternoon in 1856, hunters Gottlieb Fankhauser and Joseph Aeschlimann were standing west of the Lower Rafrüti (Emmental) when suddenly, something whizzed past them with strong flash of light and a violent boom. It was only thirty years later that Andreas Zürcher, the tenant of the alp, found an 18-kilogram object – part of the meteor that had thundered down to earth in 1856 and broken apart in the atmosphere. He assumed it was a cannonball from the transitional time between the Napoleonic Act of Mediation and the Restoration period. He sometimes heated up the stone in winter and used it to keep his cattle’s water supply from freezing or as a practical heating pad in bed. In the summer of 1900, he received a visit from a secondary school teacher by the name of Widmer. Thinking that the stone might be a meteorite, Widmer sent it to the Natural History Museum Bern. The true nature of the “cannonball” was only revealed 16 years after its discovery.

In 1984, a farmer named Margrit Christen happened upon a strange 16-kilogram stone while plowing in Gruebmatt (BE). This turned out to be part of the Twannberg meteorite. According to Beda Hofmann of the Natural History Museum Bern, it fell from the skies around 165,000 years ago and broke into pieces. The Twannberg meteorite must have weighed 1,000 tonnes, but only 150 kilograms have been found thus far. As of 2022, 1,602 samples from the Twannberg strewn field have been collected. In the first decade of the 2000s, media reports about the falling star of Twannberg inspired many volunteer meteorite hunters and journalists to scour the area – much to the chagrin of local farmers. For scientists, however, discovering the extent of the scatter field size was a sensation.

These Swiss meteorite stories – and many more like them – can be accessed anywhere and anytime at e-newspaperarchives.ch, the open access platform for digitalised newspapers in Switzerland. The Perseids meteor shower can be viewed free of charge every year from 17 July to 24 August – and can perhaps serve as inspiration for additional stories.

Bibliography and sources

- Dürrenmatt, Friedrich: [School notebook with sketches of stars – two-page spread 2],

- Dürrenmatt, Friedrich: Unheilvoller Meteor, 1980, gouache on cardboard, 71.5 x 102 cm, Collection of the Centre Dürrenmatt Neuchâtel.

- Steine fallen vom Himmel, in: Der Bund from 20.11.1938. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- “Von Sterne, die vom Himmel fallen”, in: Der Bund from 29 July 1973. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Nicht nur Sternschnuppen, in: Der Bund from 14 July 1994. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Wunschkonzert am Himmel, in: Wir Brückenbauer from 10 August 1988. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Gefahr für das Raumschiff Erde, in: Wir Brückenbauer from 8 April 1992. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Feuriges Wunschkonzert am Himmel, in: Engadiner Post from 6 August 1996. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Les Météorites, in : Journal de Jura from 14 December 1945. Accessible at e-newspaperarchives.ch (consulted on 07.07.2023).

- Der Luzerner Drachenstein wird 600 Jahre alt, in: Luzerner Zeitung from 11.09.2021, consulted on 03.07.2023.

- Mitteilungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Bern: zum Verschwinden eines Meteorits: Jahre 1871 und 1872.

- Mirasteilas Observatory

- Meteorite research at the Natural History Museum Bern

Last modification 17.08.2023

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

User services

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35