During the many years that liberals, democrats and leftists spent constructing Switzerland in their own image, few seemed troubled by the fact that women were excluded. It was not until women organised themselves and demanded equal rights that a transformation of society began which is still ongoing to this day.

The men who, in 1971, granted Switzerland’s female population a say in the country’s government were acceding to a long-standing demand: one that, in the history of modern Switzerland, was voiced first by a few individuals but then by ever-increasing numbers – and repeatedly rebuffed.

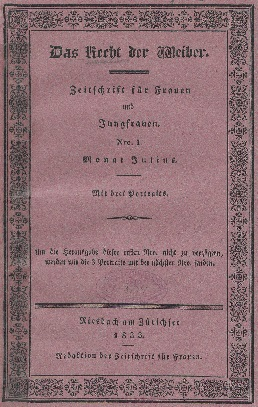

One of the earliest was the Zurich radical Johann Jakob Leuthy, who in his 1833 publication “Das Recht der Weiber” (Women’s right) asked: “Do human beings have the right to be free? Are women also human beings? Do they, therefore, have the same right to be free?”, and answered with a resounding “yes”. He was almost alone in holding that view.

A federal state with feet of clay

When the Federal State was founded in 1848, Swiss men became the first in Europe – alongside their French counterparts – to accord themselves the right to vote. Their sons campaigned for “citizens’ rights” in the Democratic Movement of the 1860s, but did not allow Swiss women to share them. For women in the 19th century, however, demands such as the abolition of gender tutelage and the removal of discrimination in inheritance law and education were issues of prime importance. Those demands, too, fell on deaf ears.

Yet there were women calling for political equality. They included Marie Goegg-Pouchoulin, from Geneva, who set up the “Association internationale des femmes” in 1869 and the (national) “Association pour la défense des droits de la femme” in Bern in 1872, together with Julie von May. These were the first feminist organisations in Switzerland. The national association first called for “the absolute equality of women before the law and in society” in 1873. Women increasingly began banding together: female workers in 1890, in the Swiss Women Workers’ Union (SAV); middle-class women in 1900 in the Union of Swiss Women’s Associations (now alliance F), and in 1909 in the Swiss Association for Women’s Suffrage (SVF, now the Swiss Association for Women's Rights).

Federal judges shun an opportunity

In 1887 the Federal Supreme Court had a chance to acknowledge women as citizens – but declined to take it. The case before them had been brought by Emilie Kempin-Spyri from Zurich, the first Swiss woman to graduate with a law degree. She was prevented from practising as a lawyer because she did not have the necessary citizen’s rights. She demanded them on the basis of Article 4 of the Federal Constitution, which stated: “All Swiss citizens are equal.” She argued that the German term used for “Swiss citizens”, although masculine in gender, also included women. The federal judges declined to interpret the law in women’s favour, arguing that to do so would run counter to the “conception of the law that, without question, still currently prevails”. Yet the court could have chosen to break with this patriarchal tradition and acknowledge the principle of legal equality.

General strike and red patriarchs

Women’s right to vote and stand for election was the second of nine demands formulated by the Olten Action Committee in its strike call of 1918. Rosa Bloch-Bollag was the only woman on the committee; she and women’s issues struggled to gain full recognition among the “red patriarchs”.

In 1928, middle-class women relaunched the campaign for women’s suffrage: at the Swiss exhibition of women’s work (SAFFA) in Bern they staged a demonstration with a giant snail, denouncing the slow pace of official action. Their petition, signed by a quarter of a million men and women, was stuffed into a drawer and forgotten about.

Parliaments, governments and a defending army

Repeated attempts were made by parliamentarians to put forward proposals in favour of women’s rights. Nevertheless, the motions by National Council members Herman Greulich (Social Democrat, ZH) and Emil Göttisheim (Radical, BS) in December 1918 as well as those in 1944 by Hans Oprecht (Social Democrat, ZH) and in 1949 by Peter von Roten (Conservative Catholic, VS) all failed. In the Cold War, Switzerland’s army of men successfully defended their power over women at the ballot box, rejecting women’s suffrage by a two thirds majority in 1959.

Break-up and breakthrough

The socio-cultural transformation of 1968 reached Switzerland too, manifesting itself, in the Catholic regions of the country, in the progressive moves triggered by the Second Vatican Council. The traditional image of the “strong man” as “protector” of women was increasingly supplanted by the ideal of the “partner”. When women’s rights campaigners organised a “march on Bern” in March 1969, they were joined by some of those same “new men”. The clear vote in favour of women’s suffrage in 1971 was “merely” the consequence of this profound upheaval – albeit one that was far from complete, as the next 50 years were to show.

Bibliography and sources

- Caroline Arni, Republikanismus und Männlichkeit in der Schweiz, in: Der Kampf um gleiche Rechte, hrsg. vom Schweizerischen Verband für Frauenrechte = Le combat pour les droits égaux, éd. par l'Association suisse pour les droits de la femme (adf-svf), Basel: Schwabe 2009, S. 20-31.

- Annette Frei, Rote Patriarchen : Arbeiterbewegung und Frauenemanzipation in der Schweiz um 1900, Zürich: Chronos 1987.

- Elisabeth Joris, Mündigkeit und Geschlecht: Die Liberalen und das «Recht der Weiber», in: Im Zeichen der Revolution. Der Weg zum schweizerischen Bundesstaat 1798-1848, Zürich: Chronos 1997, S. 75-90.

- Beatrix Mesmer, Ausgeklammert – eingeklammert. Frauen und Frauenorganisationen in der Schweiz des 19. Jahrhunderts, Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn 1988.

- Beatrix Mesmer, Staatsbürgerinnen ohne Stimmrecht. Die Politik der schweizerischen Frauenverbände 1914-1971, Zürich: Chronos 2007.

- Das Recht der Weiber. Zeitschrift für Frauen und Jungfrauen, Riesbach am Zürichsee: J. J. Leuthi 1833 (online).

- Werner Seitz, Auf die Wartebank geschoben. Der Kampf um die politische Gleichstellung der Frauen in der Schweiz seit 1900, Zürich: Chronos 2020.

- Brigitte Studer; Judith Wyttenbach, Frauenstimmrecht. Historische und rechtliche Entwicklungen 1848 – 1971, Baden: Hier und Jetzt 2021, ISBN 978-3-03919-540-4.

- Die Vorkämpferin. Offizielles Organ des Schweizer. Arbeiterinnenverbandes, verficht die Interessen der arbeitenden Frauen, Zürich: Conzett, 1906–1920.

Last modification 20.10.2021

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

Information Retrieval Service

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35