These days, environmental considerations are one more reason to use every part of a slaughtered animal. That said, the idea of consuming everything “from nose to tail” is not new, but part of a tradition which recognises that meat is a valuable resource that should not go to waste. Butchers support the renaissance of old-fashioned meat recipes.

These days, only hardcore meat-lovers still consume offal. Along with other meat specialities, it has largely disappeared from butchers’ counters. As prosperity has increased, food has accounted for a steadily decreasing share of income for people living in industrialised nations. Today, most no longer need to make do with “simple fare”.

Different parts, different prices

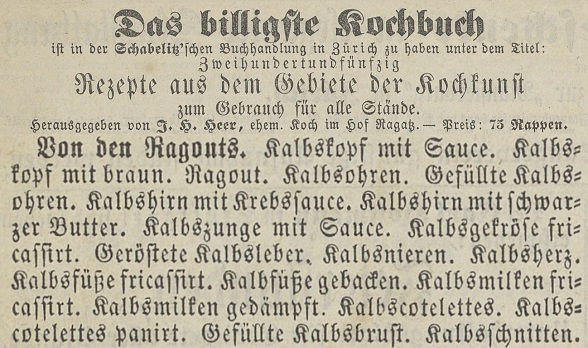

A pig is more than just ham and cutlets, while the best cuts of beef account for only around 15% of the meat that’s fit for sale. The prime parts of the animal have always been much in demand, and priced accordingly. Yet even people of modest means were not obliged to go without meat: there was a wide range of cheaper parts and a vast array of recipes for using them. This can be seen in publications such as “Das billigste Kochbuch” (third ed. in 1862), a cookery book full of instructions on how to prepare stuffed calf’s ears, pig’s trotters and the like.

Rediscovering “nose to tail”

With the advance of industrialisation, meat production has vanished from the consciousness of consumers. As we survey the neatly packaged meat products on the supermarket shelves, it is easy to forget that they were once part of a living creature. And when haute cuisine chefs reduce the ingredients to foams and essences, the connection to food’s origins is completely lost. To counter this trend, the English chef Fergus Henderson developed the “nose to tail” philosophy. It focuses on appreciation of the (slaughtered) animal, combined with the sensual pleasure of the gourmet. “If you’re going to kill the animal it seems only polite to use the whole thing”, Henderson argues in his 1999 book “Nose to Tail Eating” (published in German by Echtzeit Verlag, Basel in 2014).

New arguments for using everything

Breeding livestock consumes large amounts of natural resources, as does importing the finest cuts from overseas. So alongside the traditional motivations to be less fussy about which bits of an animal we eat, there are also good environmental reasons for doing so. “Nose to tail” has also caught on in Switzerland, and has even spawned its very own Swiss-German dialect equivalent: “Vom Schnörrli bis zum Schwänzli”.

The traditional argument that braising and stewing meat as well as eating offal saves money still applies. But preparing them often takes longer than frying a steak or putting a ready meal in the microwave. In that respect, “nose to tail” has something in common with the “slow food” philosophy, which has emerged in recent decades in opposition to fast food.

Bear meat for dinner

Meat eaters have become more choosy not just about their favoured cuts of meat, but also about the animals they come from. In different cultures and at different times, a species can be “humans’ best friend”, “disgusting”, or a “delicacy”. The level of prosperity plays a key role, but so do our aesthetic sense and feelings towards animals.

One example of this is how the people of Bern feel about the creature that adorns their coat of arms: for many years, bears that could no longer be accommodated in the city’s bear pit were slaughtered and the meat was offered as an exclusive dish in restaurants. In 1984 the mentality changed: when the director of the zoo observed in public that there was nothing wrong with using up carcasses that way, his comments were met with a storm of outrage, whereupon he ceased offering the bears from the pit to restaurants. Instead, the dead animals were sent to the disposal facility in Lyss, where they were processed into animal food and fertiliser along with other carcasses.

The former bear pit is now a bear park, and today’s bears are prevented from breeding to ensure that there are never more than it can accommodate. Today, the people of Bern bemoan the absence of cute bear cubs with the same passion with which they once objected to the slaughter of animals deemed surplus to requirements.

Bibliography and sources

- J. H. Heer, Das billigste Kochbuch! 250 Rezepte aus dem Gebiete der Kochkunst, zum Gebrauch für alle Stände, 3. Aufl., Bern: J. Heuberger 1862

- Zürcherische Freitagszeitung, Nummer 50 vom 16. Dezember 1859, Seite 6: Anzeige der Neuerscheinung «Das billigste Kochbuch»

- Fergus Henderson und Justin Piers Gellatly, Nose to Tail, Basel: Echtzeit-Verlag 2014

- Proviande: Nose to Tail (in German)

- Au-delà du filet, de l'entrecôte & Co. : constats et impulsions tirés du projet Savoir-Faire (2016-2019), Berne : Proviande 2019

- Nose to Tail: Megatrend der Fleischbranche

- Slow Food Schweiz

- ProSpezieRara: Wieso Tiere essen, um sie zu retten?

- Einheimischer Bärenpfeffer in der Mutzenstadt. In: Der Bund 135. Jg., Nr. 51 vom 1. März 1984, Seiten 1 und 25

- Kurt Hediger, Innig aber verkrampft. Das Verhältnis der Bernerinnen und Berner zu ihrem Wappentier. In: Der Bund 137 Jg., Nr. 140 vom 19. Juni 1986, Seiten 1 und 25

- Dominik Straub, Der Bär verschwindet endgültig von Berns Speisekarten. In: Der Bund 142 Jg., Nr. 187 vom 13. August 1991, Seiten 1 und 15

- History of the Centravo AG (emerged, among others, from Swiss Master Butcher Cooperative for Central Switzerland GZM)

Last modification 13.04.2021

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

Information Retrieval Service

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35

Fax

+41 58 462 84 08