Nowadays, Saint-Imier and its valley are principally associated with watches, wind farms, photovoltaic installations and chocolate. What is less well known is that this was the birthplace of the Jura Federation, the first manifestation of anarchism in Switzerland. It disappears from the scene shortly before the opening of the Swiss National Library in 1895.

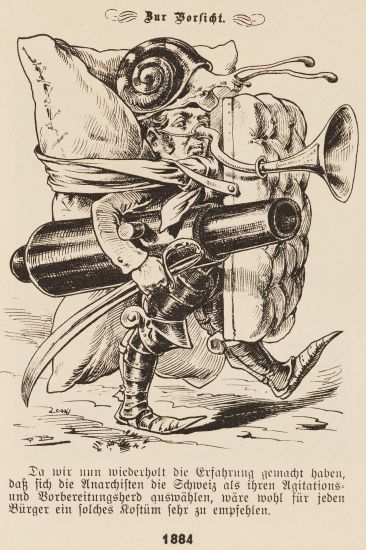

“Since we have frequently seen the anarchists choosing Switzerland as a place to agitate and prepare, every citizen should perhaps be advised to wear an outfit such as this.”

© Nebelspalter Vol. 70., Issue 41, 5 October. 1944, page 51, Fritz Boscovits

In the second half of the 19th century the Industrial Revolution is in full swing, leading to the emergence of a social stratum termed the working class. It increasingly organises itself to defend its interests, notably through trade associations and welfare funds.

Activists from various European countries establish the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA, commonly known as the First International) in London in 1864. Guided by Karl Marx, it calls on workers to unite against the ruling classes, and brings together a vast range of political creeds. Sections of the IWA flourish in many places in Switzerland, mostly where there are watchmaking factories (the Neuchâtel mountains, the Jura, Geneva, and so on).

The Jura Federation comes into being through a dispute between two factions – one represented by Karl Marx, a member of the General Council (the IWA’s executive), communist and advocate of a centralised state; and the other by Mikhail Bakunin, whose views are anti-authoritarian (arguing for the destruction and disappearance of the State) and collectivist (advocating common ownership of the means of production). Bakunin’s ideas find a ready audience in the watch factory workers of the Jura region. At the Basel Congress in 1869 the differences between the two sides become more acute.

The fall of the Second Empire and the setting up of the Paris Commune in March 1871 galvanise the members of the International, who are convinced that the time for proletarian revolution has come. These hopes are dashed, as a wave of repression is visited on workers’ movements across Europe.

It is against this turbulent backdrop that the Jura Federation is established on 12 November 1871 at Sonvilier, in the Saint-Imier valley; it becomes an anti-authoritarian, “anarchist” movement (from the Greek “anarkhia” meaning without a ruler). It rejects participation in political bodies (which favour the bourgeoisie) and insists that producers should receive the full fruits of their labour. Its propaganda organ is the Bulletin, edited by James Guillaume.

At the Hague Congress in 1872, the rift between Marxists and anarchists becomes final. Subsequently, a congress convenes at Saint-Imier in September that year. The Bulletin reports on its deliberations, and in particular the following three declarations, which sum up its political beliefs:

“[…] The Congress meeting at Saint-Imier declares:

1. That the destruction of all political power is the first duty of the proletariat.

2. That any organisation of a political power claiming to be provisional and revolutionary in order to bring about that destruction cannot but be one more deception, and would be as dangerous to the proletariat as all the governments that exist today.

3. That in rejecting all compromise in order to complete the Social Revolution, proletarians of all nations must establish solidarity of revolutionary action outside any bourgeois politics.” (Bulletin of the Jura Federation, no. 17/18)

Initially, the members of the Jura Federation are far removed from the cliché of the violent, godless and lawless anarchist. The activists’ meetings prove to be studious and peaceful. One of the leading figures, Adhémar Schwitzguébel, who is almost ascetic in his conduct, increases the movement’s determination and seriousness.

In the years that follow, the Federation’s sections develop and take part in trade union activities and help to spread anarchist ideas.

In 1876, the Bern Congress decides to step up the propaganda, which tips over into violent demonstrations. Activities to protect workers increasingly take a back seat in favour of ideological propaganda. Faced with economic difficulties, the watch factory workers abandon the movement. Without them, the Jura Federation ceases to exist in any meaningful form by around 1881. All that is left are anarchist groups which organise assassinations and insurrections across the country.

Documentary sources

- Antonioli, Maurizio. Bakounine: Entre syndicalisme et anarchisme. Paris: Editions Rouge et Noir, 2014.

- Bulletin of the Jura Federation, no. 17/18 (15 September / 1 October 1872). The two Congresses at Saint-Imier.

- Eitel, Florian: Anarchistische Uhrmacher in der Schweiz. Mikrohistorische Globalgeschichte zu den Anfängen der anarchistischen Bewegung im 19. Jahrhundert. Bielefeld, 2018

- Enckell, Marianne. La Fédération jurassienne : les origines de l’anarchisme en Suisse. Genève, Paris: Entremonde, 2012

- Kühnis, Nino. Anarchisten! : von Vorläufern und Erleuchteten, von Ungeziefer und Läusen - zur kollektiven Identität einer radikalen Gemeinschaft in der Schweiz, 1885-1914. Bielefeld : Transcript-Verlag, 2015

- La première internationale et le Jura. Colloque du cercle d’études historiques de la Société jurassienne d’émulation. Porrentruy, 1972.

- Bürgi, Markus: Internationales ouvrières. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 18.12.2013

- Gigandet, Cyrille: James Guillaume. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 13.08.2008

- Kohler, François: Adhémar Schwitzguébel. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 17.03.2011

- Kohler, François: Fédération jurassienne. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 01.10.2014

- Degen, Bernhard: Mouvements ouvriers. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 24.02.2014

- Anarchisme. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 17.06.2002

- Michel Bakounine. In: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland [online], last updated 26.03.2009

Digitized Press

Fiction

Reference institution

Last modification 14.12.2020

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

Information Retrieval Service

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35