Food security can be closely linked to the issue of political participation. This link is explored here on the basis of Switzerland’s food crisis between 1914 and 1918: women from rural and urban areas fought for the right to have their say during the First World War, and were involved in shaping important political matters.

Food is not only a physiological need, it also affects morality and politics. The link between morality, politics and food is particularly burned into the consciousness of a society when there is not enough food to supply the population. The Swiss population last faced food shortages and galloping inflation during the First World War.

As the war lasted a relatively long time (1914–18), the meagre precautions provided by the government turned out to be insufficient. In addition, difficulties in international trade led countries to largely fall back on domestic production, and to make matters worse, poor weather in key food-producing countries led to harvest failures. This disastrous combination of factors caused food shortages and catastrophic price increases for consumption as well as higher production costs, and not only in Switzerland.

Poor and powerless in towns

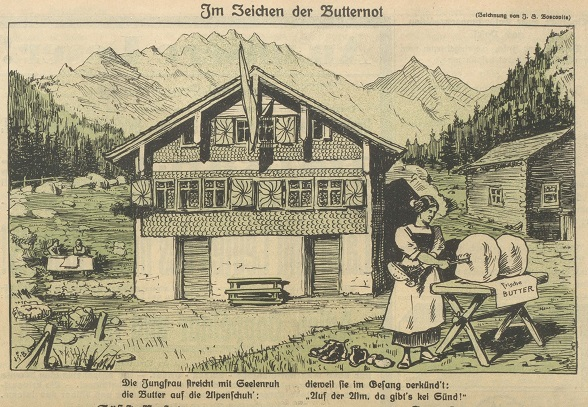

In towns, the incomes of working-class families completely disappeared overnight due to the wartime mobilisation. There was no compensation for loss of earnings during military service at the time, so female workers in towns were solely responsible for providing for their families and were powerless in the face of soaring food prices. With no political voice but fearing for their survival, female consumers in towns initially started spontaneous rebellions. From 1915, women consumers teamed up in various Swiss towns, seized goods that they considered too expensive and started selling them on their own at prices they deemed fair. In this sense, the protesters saw themselves as an extension of the police, directly cracking down on profiteering. In this combative fashion, women consumers in urban areas regained some power and spoke out against the supposed injustice, which was primarily directed against food producers, whom they perceived as greedy (cf. picture).

Overworked and voiceless in the countryside

The battle lines between urban consumers and agricultural producers seemed immutable. However, one female farmer also raised her voice in the male-dominated world of agriculture, calling for intermediary trade to be eliminated and for more direct and closer market relations between consumers and producers. She wanted the two sides to better understand each other and thus to guarantee fairer prices for both parties. This woman was called Augusta Gillabert-Randin. She set up the “Association des productrices de Moudon” (APM) with the aim of transporting agricultural products to the towns using consolidated consignments, thereby establishing direct links between producers and consumers and building mutual respect. But Randin did not only seek to ease tensions between town and country, she also worked to improve the status of women within Swiss agriculture. She was involved in the 2nd Swiss Women’s Congress in 1921, took part in the Swiss Exhibition for Women’s Work (SAFFA) with the APM in 1928, and fought for women’s suffrage in Switzerland.

Forgotten voices from history

This brief historical episode shows the close link between food security and political participation. Women were excluded from the political process both in towns and in the countryside during the First World War. On account of their wartime responsibilities, women found their political voice and fought to be heard. For a long time, this female engagement was depoliticised and marginalised in Swiss history books. Only now are these voices finding their rightful place in history.

Bibliography and sources

- Daniel Flückiger, Peter Moser: Gillabert-Randin, Augusta (1869-1940); ARH database of people and institutions, version of June 2021.

- Regula Ludi: Augusta Gillabert-Randin, in: e-HLS, Version vom 22.01.2020.

- Marthe Gosteli; Peter Moser (Hg.): Une paysanne entre ferme, marché et associations. Textes d’Augusta Gillabert-Randin 1918-1940, Baden 2005.

- Vorkämpferin : offizielles Organ des Schweizerischen Arbeiterinnenverbandes, 01.08.1916: 4-5.

- Béatrice Ziegler: Arbeit – Körper – Öffentlichkeit. Berner und Bieler Frauen zwischen Diskurs und Alltag (1919-1945), Zürich 2007.

- Getrud, Schmid-Weiss: Schweizer Kriegsnothilfe im Ersten Weltkrieg: Eine Mikrogeschichte des materiellen Überlebens mit besonderer Sicht auf Stadt und Kanton Zürich, Wien 2019.

- Daniel Burkhard: Die Kontroverse um die Milchpreisteuerung in der Schweiz während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Daniel Krämer, Christian Pfister, Daniel Marc Segesser (Hg.): «Woche für Woche neue Preisaufschläge» Nahrungsmittel-, Energie- und Ressourcenkonflikte in der Schweiz des Ersten Weltkrieges. Basel 2016: 235-255.

- Elisabeth Joris: Umdeutung und Ausblendung. Entpolitisierung des Engagements von Frauen im Ersten Weltkrieg in Erinnerungsschriften, in: Konrad J. Kuhn; Béatrice Ziegler (Hg.): Der vergessene Krieg. Spuren und Traditionen zur Schweiz im Ersten Weltkrieg, Baden 2014: 133-151.

- Maria Meier: Von Notstand und Wohlstand: Die Basler Lebensmittelversorgung im Krieg 1914-1918, Zürich 2020.

- Juri Auderset; Peter Moser: Krisenerfahrungen, Lernprozesse und Bewältigungsstrategien: Die Ernährungskrise von 1917/18 als agrarpolitische «Lehrmeisterin», in: Thomas David; Jon Matthieu; Jannick Schaufelbuehl; Marina Janick; Tobias Straumann (Hg.): Krisen. Ursachen, Deutungen und Folgen, Zürich 2012: 133-149.

Last modification 17.08.2021

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

Information Retrieval Service

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35

Fax

+41 58 462 84 08