Birchermüesli is a vegetarian dish that’s known around the world. It was invented by a doctor in Zurich in around 1900. What were his beliefs, and how did his new invention fit in with the predominantly meat-based diet of the time?

When a young doctor named Maximilian Bircher-Benner (1867–1939) opened his first surgery in the working-class Zurich district of Aussersihl towards the end of the 19th century, he encountered factories, warehouses, cramped dwellings, high levels of alcohol consumption, domestic disharmony and a diet heavy in meat. The mechanical logic of the factory dictated the daily intake: coal for the machines, protein for the muscles and a constantly smoking chimney. The sensitive physician was troubled by the lack of harmony: something seemed to be out of kilter and in need of correction.

© Hans Rausser

A new theory of nutrition

In the 19th century, the conventional nutritional wisdom was that to live an especially healthy life, human beings should eat lots of protein to optimise the supply of energy to the body. Based on his experience of prescribing raw vegetable diets to the sick, Bircher soon came to doubt the efficacy of this meat-based approach. He developed his own nutritional theory centred around “sunlight value” as a yardstick for measuring the quality of food. He believed that quality rather than quantity was at the heart of the science of nutrition, and that raw fruit and vegetables were most nutritious since they still contained energy from the sun in its most unadulterated form. As vegetables were cooked, he believed, that energy was gradually lost. Meat, meanwhile, was entirely dead organic matter: during their lives, animals absorbed energy from the sun through the plants they ate, but used it all to sustain their own organisms. For this reason, Bircher thought, the meat obtained from animals had no qualitative energy left and was the lowest-quality form of food.

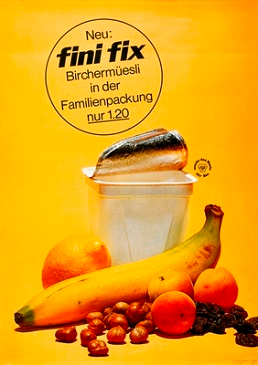

A müesli for the world

In his sanatorium on the Zürichberg, Bircher developed an apple diet dish based his nutritional theory which he referred to simply as “d’Spys” (the dish). The recipe calls for a tablespoon of sweetened condensed milk, the juice of half a lemon, a tablespoon of softened oats, a tablespoon of grated nuts and a large apple which – peel, seeds, core and all – is then grated and mixed with the oats, lemon juice and condensed milk. The nut mixture can then be sprinkled on top.

Bircher argued that this dish contained the same proportions of protein, fat and carbohydrates as breast milk and was also akin to the diet of Swiss mountain shepherds, whose reputation for robust health had been cemented by Johanna Spyri’s “Heidi”.

If its creator is to be believed, Birchermüesli is nothing short of a superfood. At any rate, since its invention in around 1900, it has become popular the world over. The Swiss-German term “müesli” is also the only word from the dialect to have entered numerous languages around the globe.

Raw vegetables and healthy living

The discovery of vitamins in the early 20th century would lend scientific backing to Bircher’s approach, but the vegetarian doctor was derided by orthodox medicine in the 19th. He was, however, much admired among the “back-to-nature” movement. The critical belief that a world of mechanisation and industry was plunging civilisation into chaos and sickness was widespread at the turn of the 20th century. The back-to-nature movement brought together an eclectic mix of vegetarians, agrarian reformers, abstainers, Freiwirtschaft economists, anarchists and, from time to time, adherents of ethnocentric and occult beliefs, all united by their opposition to the prevailing materialism – a kind of green movement avant la lettre.

This was where Bircher found his spiritual home. His magnum opus, “Der Menschenseele Not” (1927−1933), is a psychological and philosophical work that is part lament for the state of the world and part expression of reformist optimism. At its heart is the fundamental physiological conviction that “you are what you eat”.

Bibliography and sources

- Der Wendepunkt im Leben und Leiden: eine schweizerische Zeitschrift zur Verbreitung nützlichen Wissens über das Leben des Körpers und der Seele, über Wesen und Erhaltung der Gesundheit, über Ursachen und Natur der Krankheiten, über Heilprozesse und Heilkräfte (1923-1978)

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner: Prospect des Centralbades, Zürich 1901.

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner, Kurze Grundzüge der Ernährungs-Therapie auf Grund der Energie-Spannung der Nahrung, Berlin 1903

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner, Vom Werden des neuen Arztes, Dresden 1938.

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner, Ordnungsgesetze des Lebens als Wegweiser zur Gesundheit, Drei Vorträge gehalten in London, Zürich 1938.

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner: Der Menschenseele Not, Band 1: Erkrankung und Gesundung, Zürich 1927.

- Max[imilian] Bircher-Benner: Der Menschenseele Not, Band 2: Erkrankung und Gesundung, Zürich 1933.

- Ralph Bircher: Bircher-Benner, Leben und Lebenswerk, Neuausgabe von 2014 [Erstveröffentlichung 1959], Braunwald 2014.

- Albert Wirz, Die Moral auf dem Teller, Zürich 1993.

- Caroline Jagella-Danoth: Maximilian Oskar Bircher-Benner, dans: e-HLS, Version du 03.11.2010

- Roman Kurzmeyer: Mouvement pour une vie saine, Dans: e-HLS, Version vom 03.07.2012

- Joachim Radkau: Die Verheissungen der Morgenfrühe- Die Lebensreform in der neuen Moderne, In: Kai Buchholz, Rita Latocha, Hilke Peckmann (Hg.): Die Lebensreform. Entwürfe zur Neugestaltung von Leben und Kunst um 1900. Darmstadt 2001: 55-60.

- Thomas Rohkrämer: Lebensreform als Reaktion auf den technisch-zivilisatorischen Prozess, In: Kai Buchholz, Rita Latocha, Hilke Peckmann (Hg.): Die Lebensreform. Entwürfe zur Neugestaltung von Leben und Kunst um 1900. Darmstadt 2001: 71-73.

- Eva Barlösius: Naturgemässe Lebensführung, Zur Geschichte der Lebensreform um die Jahrhundertwende, Frankfurt am Main, 1997.

- Rindlisbacher, Stefan: Die Schweizer Lebensreformbewegung: Anleitungen für ein «besseres Leben», In: Bernisches Historisches Museum (Hg.): Lebe besser! Auf der Suche nach dem idealen Leben, Begleitpublikation zur Ausstellung(13.02.2020-05.07.2020), Bern 2020.

Last modification 22.02.2021

Contact

Swiss National Library

SwissInfoDesk

Information Retrieval Service

Hallwylstrasse 15

3003

Bern

Switzerland

Phone

+41 58 462 89 35